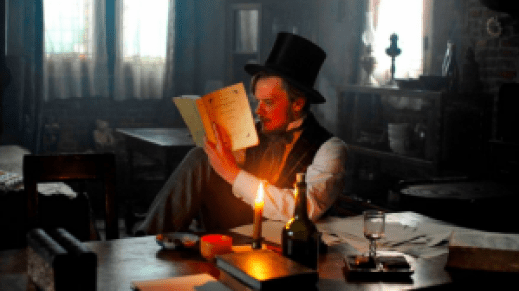

Raoul Peck directed one of the best movies of 2017 in I Am Not Your Negro, his documentary about the titanic writer James Baldwin. Compared with that film, The Young Karl Marx seems on the surface like an ornate costume drama of deep intrigue. Mostly it succeeds at that, but the compression of time during Marx’s political organizing undermines the long story development before the moment where his and Engels’ doctrine or tactics are accepted.

The film focuses on the tension around Marx and Engels’ differing socio-economic status, and the way Marx’s radicalism gave structure and motivation to Engels’ emotional responses to the suffering witnessed.

Poverty is an enveloping cloud of dust around almost everyone in the film. The wealthy are painted not with simply foaming, exploitative malice, but as genteel and not used to being questioned on their assumptions and attitudes (aside from Engels, who starts out as a dandy and an interloper). My experience tells me that Americans seem to feel that they can always be saved by being polite to their oppressors, but the pivotal scene of this film appears to me to be the moment where Karl Marx (August Diehl) is simple and direct in disagreement with a wealthy, anti-Semitic peer of Engels’ family. This is where the influence of the Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro is felt, in my view, since Baldwin’s focus on confrontation and blunt engagement with issues parallels Marx’s personal style in The Young Karl Marx.

The sense of being hunted and hounded, first by poverty and then by state repression of revolutionary or even critical ideas, is used to exceptional effect, as Marx and the heroic class traitor Jenny von Westphalen are driven first from Germany and then Paris, as Karl attempts to make a living to feed his family in now in Brussels away from their home in Germany with his writing and then in the postal service. The contrast between Marx and Engels becomes stark, and clarifies the roots of Marx’s radicalism. The clear structure of there being two worlds—one of proletariat Marx and another of bourgeois Engels—is a very effective rendering of Marxist dialectical materialism and creates compelling dramatic tension between the two.

All of this leads to a reveal that places Marx and Engels in a leadership position in “The League of the Just”—which appears to serve very efficiently as a working-class leftist infighting group—whose congress the two are to attend. The moment when Marx and Engels triumph over the reformist factions in the League struggles to make clear the work it had taken to arrive there, but on the other hand, the audience is not subject to any extended “I AM WRITING AND STRUGGLING WITH IMPORTANT THINGS” scenes, so I suppose as a filmmaking technique, especially in a movie that comes in just under two hours as it is, Peck made the correct choice in favor of dramatic tension over development.

It can be tough to depict political organizing onscreen both accurately and in ways that are interesting to view, so it is to the film’s credit that the transformation is left at the meeting and the fallout only discussed in epilogue text cards. The onrush of the “inevitable proletariat revolution” in Europe is certainly dramatized in the closing scenes of negotiation at the League Conference, and the seizure of power among the league is staged with both triumph and disdain among the factions in the meeting, and the sense of simultaneous loss and celebration of possibility was keenly felt in my viewing, even as the discussion of the multinational 1848 workers’ revolutions in Europe printed on the black screen. The film felt both historically accurate and like an adrenaline rush that may make players in such a political game misinterpret what they see in Marx, which history has shown to be just as much of a struggle as the one among the classes. Polemic can be fun, and The Young Karl Marx showed that enduring polemic usually comes from people’s lives and experience, regardless of what the haters say.

–Lee Pietruszewski

Leave a Reply