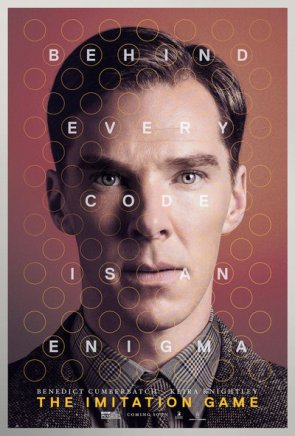

The opening voice-over from The Imitation Game features Benedict Cumberbatch telling everyone to look closely at what’s about to come. It’s all a game, Cumberbatch says. “Are you paying attention?”

The opening voice-over from The Imitation Game features Benedict Cumberbatch telling everyone to look closely at what’s about to come. It’s all a game, Cumberbatch says. “Are you paying attention?”

Cut to, oh, 90 minutes later. We dutifully return to the voice-over; this time we see Cumberbatch as Alan Turing sitting across a table from a detective. Turing, sad-eyed and exposed, asks the detective the same question we received, “Are you paying attention?” It’s a predictable and necessary moment, given what kind of movie The Imitation Game is: a fine looking, occasionally moving film that does not do justice to the riveting the source material upon which its based.

Audiences are given a hand-holding walk through three separate eras in the life of Alan Turing: one year as a schoolboy discovering his sexuality, his wartime code-breaking efforts, and his post-war life as a professor prosecuted for indecency. With the exception of Benedict Cumberbatch, surprisingly little is asked of anyone in The Imitation Game.

Alan Turing is a British mathematician who worked as part of a secret government project to break the ‘unbreakable’ Nazi code in World War 2. Germany had developed the Enigma Machine to send and decrypt coded messages. The machine allowed the Nazi’s to change the code every night at midnight. Without the Enigma machine, code-breakers had 24 hours to break a code before all their work became useless.

Rather than attempting to break a new code everyday, Turing envisioned a machine that could break every code, every day, forever. With his small team of cryptologists, logicians and cross-word puzzlers, Turing worked for years in a converted radio factory building the machine that eventually broke Enigma and paved the way to the modern computer.

Turing was a brilliant mind, and Cumberbatch plays him during the “war era” as a secretive, impersonal genius. He works simultaneously for an irascible army man, Commander Deniston (Game of Thrones Charles Dance, yet again, unlikable) and the MI6 Agent behind the secret government operation, Agent Menzies. The two follow their prescribed paths for a movie about a forthright genius: Denniston has no patience for Turing’s arrogance; Menzies enjoys the gamesmanship of covert operations, and sees in Turing the genius who can win Britain the war. One of Turing’s team members, a woman named Joan Clarke (Keira Knightley), helps Turing break out of the protective, awkward shell his intelligence and sexuality have created. Eventually, in the course of their work in the war, Joan and Alan become engaged.

The scenes portraying the politically, socially, and technically laborious code-breaking operations are the best in the film. Cinema has never met a World War 2 story that does not translate well, and in this case, the film ably captures the weight of the project and the genius of Turing in the traditional wartime drama style The Imitation Game wishes it could be.

But there is more to the story. Turing was also a gay man, which during his lifetime was illegal in Britain. This fact is the subject of the two non-wartime story arcs that The Imitation Game portrays. One shows a few months of his youth at preparatory school, where he met a fellow student named Christopher who taught him about cryptology. The two developed a loving bond cut too short. The other depicts Turing in 1952, as a police investigator suspects Turing may be a Russian spy. He instead discovers Turing is gay.

The three timelines are inter-cut throughout the film to little success. The Imitation Game struggles greatly when trying to “understand” Turing’s “personal difficulties” as rooted in the lost first love of childhood, making choices so obvious they drain the story’s humanity. The story of a young boy’s sexual discovery overlay’s a man who is has his sexuality discovered and prosecuted by others. The trials of youth allowed Turing to achieve great things against great odds. This is the film’s LESSON (it’s impossible to miss this lesson, as it is repeated word for word three times in the film).

Morten Tyldum strives to portray the human complexity in the tragic outcomes of these narratives, but his real interest is Turing’s work on the Enigma Machine-and understandably so. One could hardly imagine a more made-for-the-movies story than a secret wartime operation of Allied efforts to break Nazi code that also includes the invention of the prototype for the modern computer (Michael Apted’s 2001 thriller Enigma does a better job with this story).

All of this is particularly disappointing because Alan Turing is a remarkable, fascinating, and important figure of the 20th century. One whose accomplishments in the war effort and contributions to modern technology can hardly be overstated, and whose treatment by the British Government could hardly have been more appalling and tragic (in 2009, Britain’s Prime Minister apologized on behalf of the nation for what was done to Turing; Queen Elizabeth issued a posthumous pardon in 2013).

While The Imitation Game looks great-the photography by Oscar Faura is lovely-and contains great performances by Benedict Cumberbatch (in a Certified Award Season Performance) and Keria Knightley, I couldn’t help feeling that Turing deserves a better movie than this. A movie that does not order me to pay attention but rather grabs my attention and does not let it go. With a few brief exceptions, The Imitation Game did not even come close.