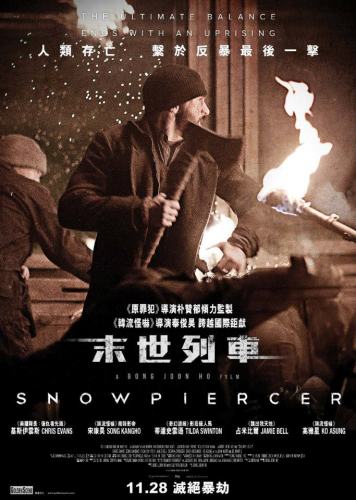

The story of Snowpiercer‘s American release has been much written about in the past year, but I think it bears quick repeating in case you haven’t heard. The film was made by the South Korean director Joon-Ho Bong (The Host) and released in Korea in August 2013, where it was wildly successful, smashing box-office records. As its release rolled west, the film continued to be a big draw with audiences, and started slowly raking in rave reviews in the US. Starring none other than Captain America‘s Chris Evans and a familiar cast of western actors-Tilda Swinton, Octavia Spencer, John Hurt-it was always going to get to the States eventually.

Enter Harvey Weinstein, who gobbled up the film’s distribution via The Wienstein Company, and quickly adopted that dreaded notion that has been ruining Asian films for decades: to edit the film for American audiences. Weinstein planned to cut 20 minutes from the film and add explanatory voice-overs at the film’s beginning and end, to, in maximum condescending asshole fashion, “ensure the film would be understood by audiences in Iowa and Oklahoma.” The short end to this story is this: Joon-Ho Bong would not allow the film to be cut, and Harvey W. failed to make his edits. The film was delayed for months until a compromise was reached, last month: the original cut of Snowpiercer was released this past weekend, but only in a limited theatrical release.

The reason this back-story is significant is that Snowpiercer, a post-apocalyptic science-fiction climate change parable of violence and inequality, is a masterpiece. To have cut it down would have been tragic. Sorry Iowa and Oklahoma. You’re missing out.

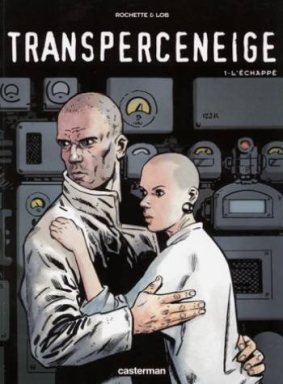

Snowpiercer is an adaptation of the 1982 French graphic novel Transperceneige, and is a pretty straight-forward revolution narrative as far plots are concerned. The film opens 18 years after humanity’s failed attempt to solve the climate crisis through geo-engineering. In order to protect life on earth, an attempt is made to create atmospheric balance by pumping a substance called CW-7 into the air. This plan fails catastrophically, bringing a new ice age that kills everything on earth. The only life remaining now inhabits a train running a 24,000 mile circuit around earth’s frozen continents. For 18 years life has been lived completely on the train. Those in the charge of keeping the train in service, supplying food and water and managing the peace, are obsessed with maintaining what could not be managed outside the train: balance.

“A closed ecosystem” is the refrain often heard, and balance on the train is everything. This includes the very close maintenance of population, class and purpose. All of which is embodied in the train itself. At the front of the train is the “sacred engine,” which makes all life possible, and Wilford, who created and runs the train and is worshiped as a God by many. Behind Wilford is the mile-long train, with cars occupied in descending class order. The front-enders live in luxury, eating steaks and getting perms. There are cars devoted to fine-dining, and dance-clubs, and spas. The middle cars are dedicated to services: food preparation, managing fish and wildlife, water purification and distribution. And the rear cars house the poor and destitute; slave labor for the front-enders.

The tail-enders live in squalor and filth, crammed into a car like sardines, surviving on protein bars served by the armed police of the train. And so the revolution at hand is set: a man, Curtiss (Evans) will lead an advance of the tail-enders from the last car to the front. Fighting and killing (and killing and killing) anyone in the way until they finally take over the engine. Take the engine, Curtiss says, and you take the train.

All of which requires a major unsettling of the the train’s careful balancing act.

So far Snowpiercer may sound like a straight-forward political allegory; the dangers of climate change, the arrogance of human technology, the perils of economic inequality, revolution. These are all poignant story qualities, appropriate for the world we currently inhabit and they provide an exciting social setting for the story that unfolds. But these are not the qualities that make Bong’s film a masterpiece. These thematic characteristics are the winter parka of the film, keeping us cozy and situated in a familiar outfit as we trundle into the unknown.

It is the trip into the unknown that makes Snowpiercer a masterpiece. Bong (and everyone involved; a movie this good is not made alone) is partaking in film-making at its most exciting. Both in style and content, Bong’s sci-fi vision of life on the train is marvelous and full of surprises, and executed in a cinematic fluency that is a wonder to behold. The cinematic fluency is especially necessary because Snowpiercer, along with being excellent, is also really weird.

Weird like this is hard to put into description, but fans of science-fiction will recognize the footprints of this kind of weirdness. The gritty images and stilted, unnatural movements of the old Jean-Pierre Jeunet films are notable in the tail-end scenes. Delicatessen came to mind several times in the film’s opening act. So too, City of Lost Children, which bears more a than few similarities to Snowpiercer.

The other, perhaps more obvious referent for Snowpiercer is Terry Gilliam’s work, particularly Brazil. Comparisons to Gilliam’s 1985 madcap psycho-sci-fi movie have been made by other viewers (it’s not hard to make the connection with the aging leader being named Gilliam and all). Both films seek to right a social disorder that has settled immovably over a society in turmoil and both find an almost unbearably bleak world of horrors resulting. The hymn-leading school-teaching Alison Pill turns in a performance that easily could come out of Brazil. All smiles and hand-gestures and utterly terrifying.

Luckily for viewers, Snowpiercer is smarter and better executed than Brazil (which is, prepare yourself, overrated). I love both Gilliam and Delicatessen/City of Lost Children, but they rely on quirky character and weird but stunning visuals and settings to hide larger storytelling faults. Watching Brazil, I never really get the sense that Gilliam is working towards a purpose beyond his own creativity and vague social notions. Joon-Ho Bong, on the other hand, has his bizarre qualities well-contained and organized. Everything is impossibly ridiculous and terribly realistic. It is, not surprisingly, balanced.

Bong has style and story in his craft. I felt the purpose in all aspects of the weird he puts on display. The film opens in a visual bleakness, cold and hard in both image and content. The horrible images of punishment when a man’s arm is frozen outside the train, paired with the Tilda Swinton’s admonishment to the tail-enders that they remain in their place to maintain ecological balance (“Be a shoe!”) is simultaneously funny and awful and perfectly sensible in the moment. (Tilda Swinton, by the way, reveals a new level here, and this is Tilda Swinton we’re talking about).

The missing limbs and off-beat speeches and extreme axe-hacking violence make for dark comic effect in the first hour of the film, only to become realized as monstrous realities beyond what we have begun to imagine. The levels of horror Snowpiercer breaches continually increases, and the nightmare that is life on the train only becomes clear as the film’s colors brighten and playfulness increases in the front-end cars. Light and dark are a thematic and visual game in the film, as the train enters and exits tunnels, and the design elements and photography involved are beautiful but rarely gimmicky.

I’m focusing on the balance here, which I realize is not an unusual characteristic in storytelling. Parallel structure in story was not invented by Snowpiercer. But execution is what makes this film special, and it’s hard to imagine a film more thoughtfully weighted in its formal accomplishments and story components. Front-back rich-poor power-powerless. Comic becomes horror; weird becomes familiar. Light and dark, violence and retaliation, eggs and bullets, shoes and hats, drugs and bombs, detail after detail is revealed from the tail-end to have its companion on the front.

I’m focusing on the balance here, which I realize is not an unusual characteristic in storytelling. Parallel structure in story was not invented by Snowpiercer. But execution is what makes this film special, and it’s hard to imagine a film more thoughtfully weighted in its formal accomplishments and story components. Front-back rich-poor power-powerless. Comic becomes horror; weird becomes familiar. Light and dark, violence and retaliation, eggs and bullets, shoes and hats, drugs and bombs, detail after detail is revealed from the tail-end to have its companion on the front.

The accomplishment of Joon-Ho Bong, his actors and film-making team in Snowpiercer, is one of pure craft, and it is a stunning reminder of the old film-school adage that Form = Content. The story is how you tell it. And Snowpiercer is a study in formal technique as story: a visual feast of unexpected surprises and technical prowess that leads audiences with such utter confidence towards a conclusion that slowly reveals itself to be the only option left. And even when that story falters, which it does, Bong has more than enough happening to keep up interest. It is the kind of experience you hope for when you sit down in a theater, to be excited for 2 hours, and left wondering how that all happened.

Snowpiercer truly is a tightly balanced ecological system. Everything in its place. A masterpiece. I don’t know what 20 minutes Harvey Weinstein could possibly have wanted to cut, but we are lucky he didn’t. It very likely could have thrown the whole thing out of balance.

Pingback: Snowpiercer The Oddest, Most Awesome Sci-Fi Release In Decades Hits Oct. 21

Pingback: Snowpiercer The Oddest, Most Superior Sci-Fi Launch In Many years Hits Oct. 21 | TiaMart Blog