I’ve got a little quiz for you.

I’ve got a little quiz for you.

Consider the following: A man who thinks himself wronged by everyone in his life lashes out, punishing the world for his sense of grievance in an act of terrible and monstrous evil that destroys everyone in its wake but also, perversely, ensures that his name will live forever in infamy.

Now, here’s your question: What story am I describing? The plot of AMC’s Breaking Bad, one of the most beloved and acclaimed television series of all time—or the true story of Elliot Rodger, the man who went on a killing spree in an act of imagined vengeance on all womankind for spurning him?

Trick question. It’s both.

After an act of senseless violence, there is no shortage of theories about why it happened, what could have been done to prevent it, and how we can change our culture to prevent it from happening next time. Inevitably, such conversations often turn to pop culture, with the question: What about the stories that we as a society choose to tell ourselves and entertain ourselves with? Might they have anything to do with this?

The debate following the UCSB shooting has been no exception. The attitudes of male privilege and sexual entitlement that were evident in the killer’s statements before the tragedy inspired the #YesAllWomen hashtag, in which women shared stories of the ways that they are targeted by misogyny and male hostility every day. From Twitter, the discussion spread far and wide, until it turned inevitably—and rightly, I think—to the ways that pop culture may or may not be complicit in this culture of male sexual entitlement that seems so rampant. Ann Hornaday penned a column in WaPo reflecting on, among other things, “frat-boy fantasies like Neighbors,” while at The Daily Beast, Arthur Chu took on nerd-gets-the-hot-girl narratives in The Big Bang Theory, Can’t Hardly Wait, and other pop culture texts.

To such pieces, the response of those in the entertainment industry is often to decry any purported link between entertainment and real-world violence—that was exactly how Judd Apatow and Seth Rogen responded to Hornaday’s column, for instance. (Hornaday’s response, for what it’s worth, was perfect.) But this defense is self-defeating—if there is truly no connection between entertainment and the bad we see in the world, then it can claim no responsibility for doing good, either. Does art really accomplish nothing? This is an argument that artists and audiences alike should reject.

Worse than self-defeating, though, arguments against linking pop culture and violence frequently rely on a straw-man: the notion that someone is arguing for a direct link between a single cultural text and a specific real-world atrocity, in this case, a causal relationship between a movie like Neighbors and the madness that drove Elliot Rodger to kill. In reality, Hornaday and Chu are arguing no such thing—if anything, what they’re asking us to notice isn’t causation, but correlation.

I’d like to do the same thing today with Breaking Bad, and with the pervasive cultural myths it partakes of and from which it draws power: the myth of the aggrieved and ill-used man, the myth of the charismatic and brilliant antihero, the myth of a great and monstrous evil, and the myth of terrible and awe-inspiring violence.

Let me be clear: I do not think that Breaking Bad is to blame for the lives that were destroyed at UCSB. Nor is Vince Gilligan. Nor Bryan Cranston, Anna Gunn, Aaron Paul, or the good people at AMC. None of them caused any of this.

No, what I want to draw your attention to is not causation, but correlation—the possibility that this insane killer and this brilliant television show are both, to some extent, phenomena springing from the same cause, symptoms of the same cultural sickness.

Breaking Bad takes as its ostensible topic the nature of evil. It’s right there in the title. The most well-known modern perspective on evil comes to us from Hannah Arendt: evil is banal, it is small, it is petty. “Only the good has depth and can be radical,” she writes. But Breaking Bad, intentionally or not, takes the exact opposite view: it is the good that is banal, weak. Evil makes us large. (Or, if you prefer: monstrous.)

That’s an oversimplification of the show’s worldview, of course, but consider for a moment the character arc of Walter White: he begins the series as what men’s rights activists or pickup artist culture (two communities with which Rodger was sadly familiar) might call a beta male. Walt is a good man, a high school chemistry teacher, but he’s also weak and ineffectual. People walk all over him—including, crucially, his wife. He’s lower-middle class, cheated (he thinks) out of a fortune by a former business partner who stole his idea and his girl. Then, driven by desperation and a cancer diagnosis, he begins cooking meth and descending inexorably into evil. And the more evil he becomes, the stronger he is. The “good” life Walt had before is banal and humiliating compared to the exhilaration of his new life of violence and power. Once a beta, Walt becomes an alpha—and one gets the sense that through it all, he’s avenging himself on the world (and, yes, the women) that used him so poorly.

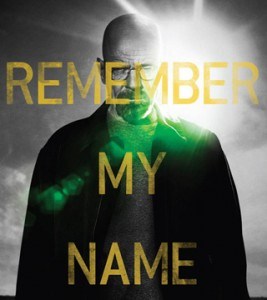

In the final season of Breaking Bad, Gilligan and his stable of writers had taken Walt so deep into the heart of darkness that there was the growing sense as the show drew to a close that the story must end with some kind of terrible and awesome climax. AMC, for its part, played into these expectations with its final season tagline: “Remember My Name.” Of course, the reference here is to Heisenberg, Walt’s meth-dealer persona—that’s the name that will be remembered—but the similarity between the marketing campaign’s promise of a final, decisive act of great and monstrous violence as a vehicle for Walt’s neverending infamy, and the final testaments of any number of random shooters, is chilling. Isn’t that, ultimately, what all these mass killers ultimately want? To be remembered by those who they think have done them wrong? For the world to look on their awful works, and weep?

Of course, to draw too straight a line from Breaking Bad to the UCSB shooting is to make the erroneous argument of causation that I’ve spoken about, and to make light of real tragedy. The point isn’t that Breaking Bad is an evil show that somehow made the world a worse, more dangerous place. In fact, many might argue that the show, to the extent that the show partakes of these narratives of male grievance and entitlement and violence, does so in order to critique them. On some days, I might be among them.

But for today, the point is that this stuff—these narratives from which sick, empty people drink so deeply and uncritically before they do horrible things—are all around us. Everywhere we look, we see cultural images of men avenging themselves on the world through acts of awe-inspiring violence. On Game of Thrones, we air our shock at the Weddings Red and Purple, then valorize George R.R. Martin for creating a world of such delicious, awesome cruelty. In Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy, we root for the Batman but take delight in the monstrous, charismatic portrayals of evil in R’as al Ghul, the Joker, and Bane. And on the news, when a madman takes to the streets to shoot strangers, we pore over his final manifesto. Isn’t it creepy? Wasn’t he crazy? There sure are some evil people in this world.

This stuff is in the water. Men who take from a world that fucked them over, badass antiheroes, awe-inspiring villains, redemptive violence. It’s everywhere. Give it to enough people and tell them to drink, and most of them will turn out just fine. But a few will be monsters.

Let’s not blame our entertainment, nor our entertainers, for the actions of these few monsters. But let us neither pretend that the one has nothing to do with the other—to indulge the pleasant fantasy that our monsters always act alone, and that the culture we’ve made together has no hand in creating them. The prevalence of these narratives of great and monstrous evil is a symptom of our demand for them. Violence sells because we keep paying for it. And monsters will exist as long as we keep finding them worthy of our awe.

Which means that if we want to change our world for the better, it’s time to start asking for better stories.