I had hoped to write a Backwoods Netflix post about The Host, given that I am a fan of the film’s director, Andrew Niccol. I had hoped that, despite the source material and terrible reviews, the film might have been a little sci-fi gem that audiences avoided because of a Twilight hangover. Alas, it isn’t so.

I had hoped to write a Backwoods Netflix post about The Host, given that I am a fan of the film’s director, Andrew Niccol. I had hoped that, despite the source material and terrible reviews, the film might have been a little sci-fi gem that audiences avoided because of a Twilight hangover. Alas, it isn’t so.

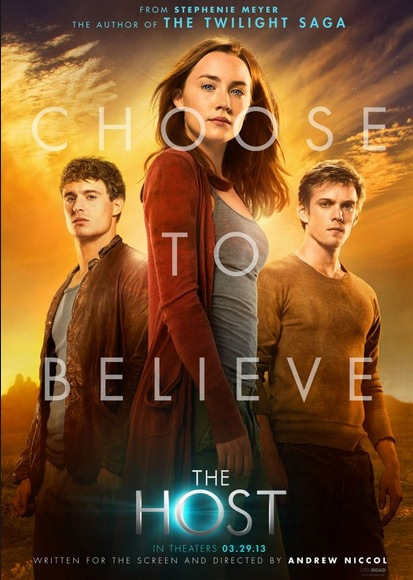

First things first then: The Host, the 2013 science-fiction body-snatcher drama adapted from the Stephanie Meyer novel, is a terrible, terrible film. With the success of The Hunger Games, and Hollywood’s search for the next great Young Adult series to adapt-I’m sure the studio hoped for a series to match Twilight. Instead, The Host serves as a lesson in how fast a bad movie can be forgotten. Did I mention this movie’s bad?

I haven’t read Stephanie Meyer’s novel, but based solely on the film I can confidently say I have no idea what the appeal of this story is. The film provides no direction to viewers unfamiliar with the story; from the first scene The Host makes no attempt to situate viewers in what is going on, and from there it wildly veers off what rails it was laid upon.

Still. I spent an evening watching and thinking about The Host, and admit there are certain delights to be found. Andrew Niccol’s noir/sci-fi pastiche remains a visual feast, for example. While gazing at the detailed and lovely future-scape it presents, and enjoying the one great scene in the film (farming with mirrors), I was reminded of a Roger Ebert review I read sometime in the past 15 years, in which Ebert related Howard Hawks’ definition of a great movie. A great film, Hawks said, has at least three great scenes and no bad scenes. I’ve always liked this definition; it simultaneously acknowledges how difficult it is to make a great movie–three scenes does not seem like that high of a bar–and how rare it is to find a movie that, start to finish, has no missteps.

Gattaca, Andrew Niccol’s 1997 debut, is an excellent example of Hawks’ definition: it has 3-5 truly great scenes, and not a single bad scene. Gattaca is a model of high-concept science fiction: it takes an intriguing concept and tightly weaves a gripping story around smart writing and skilled acting. It’s a creative and efficient piece of film-making, and is not just for sci-fi fans. So before we get to Andrew Niccol’s weakest film, let’s remember his strongest.

In Gattaca, the individual human has become the sum of his or her genes. Genetic information is readily available and the right code means everything. Job applications are pass/fail based on genetic content–you either have what it takes or you do not. Potential mates exchange hair follicles, which are then processed for a full report detailing the birth and future of your possible partner. The social network of the future is your DNA. The life you can attain is determined by what you are made of, and if you are wealthy, you are made of the best material your doctor has at hand. The rest are left with what chance provides, the luck the genetic draw.

Central to the success of Gattaca is the establishment of the Andrew Niccol visual aesthetic, which is present in every film he has directed. Niccol roots his vision of the future in the past. He mixes the idealized future as dreamed of in the 1950s, helpful technology, uniform clothing, chrome decor, crisp architecture, with the increased social and economic division that accompanies this progress: classism, poverty, desperation. The world is brighter and bluer for the rich, and darker and fully saturated for the poor. A future dystopia that, depending on the angle, could easily be mistaken for utopia.

The question of Gattaca is this: if a human life is pre-determined at birth, can we ever be more than our genes? Can we fall in love not with genes but with a person? Can we overcome the determinism of our genetic codes? The answer of course, is yes. The capacity of human achievement, love, sacrifice, these things cannot be reduced to our elemental DNA. Men and women achieve greatness all the time; their is no genetic marker for will. It’s a lovely story, beautifully told, in a powerful film.

Since Gattaca, Niccol’s work has sought to grapple with similar questions: What makes us human? How do humans live and love and interact meaningfully in a deterministic world? Are we free to make our choices, or are they made for us? These are interesting questions apt for our time, and worthy of a sci-fi director’s career.

Yet Andrew Niccol’s work is unsteady. His first film, Gattaca, remains his strongest cinematic achievement. Niccol also wrote the excellent Truman Show, and wrote and directed the pretty good S1m0ne and the very underrated Lord of War. 2011′s In Time was perhaps Niccol’s best sci-fi story concept, though the film was, to that point, his weakest.

Until The Host.

The Host finds the earth overrun by insect-like alien parasites. A full scale occupation is underway. When these parasites attach as planned, the host body is dead (or at least dormant), but the parasite–called a “soul” and occupying the area around the brainstem–can access the host’s memories. As the movie opens this has happened all over the world. Alien-infected bodies outnumber remaining humans 1,000,000 : 1. Sometimes, however, the process goes awry and the host brain remains active and cohabitates alongside the parasite/soul.

This is the situation for our bi-polar heroine(s), and sets up the film’s long running internal dialogue between a teenage girl named Melanie and a 1,000 year-old interplanetary traveling caterpillar named Wanderer. The two bond, for some reason that is never explained, and they run away from the alien-hosted facilities to seek out Melanie’s human pals to save them before they are similarly implanted. This is all explained dutifully in absolutely boring exposition in the first 10 minutes of The Host.

The remaining 115 minutes is a mixture of nearly incomprehensible emotional responses to awkward teen romance, punctuated by appearances from unenthusiastic “Seekers” searching for the rogue Wanderer.

There is some potential in the strange conceit in The Host, but Niccol turns his focus mainly to the Stephanie Meyer love-triangle obsession, which reaches almost Twilight-levels of ridiculousness. Two creatures of different species, inhabiting the same body and brain, in love with two different boys. You would think a creative film-maker like Niccol could make something of such an unusual teen-romance set-up, but such opportunities do not materialize. Instead we are left wondering why a 1000 year-old alien parasite who has lived on 8 different planets and been randomly inserted into a young human girl would fall head-over-heels in love with a teenage boy immediately following their introduction. (This question haunted me the entire film. WHY!!!)

But the biggest sin of The Host is not that it is bad–bad can be quite enjoyable, even Stephanie Meyer can be trashy fun (see the awful Twilight finale)–but that it is simply boring. The humans in hiding do nothing but chatter about hiding, and even the alien “villains” only halfheartedly pursue the object of their super-important search. Why would anyone care about a story when even the participants in the story don’t care? It’s all terrible, and stupid.

And yet, I can see why Niccol chose to make The Host. At its core, The Host is a story about being, and remaining, human. The film unfolds on a backdrop of the Andrew Niccol visual aesthetic–the same future he envisions in Gattaca and elsewhere-and it looks stunning. And If you can ignore the Stephanie Meyer-ness and see rather an avenue for Andrew Niccol to parlay with the large questions of his work, it is possible, at the very least, to enjoy the The Host as a reflection on the Niccol’s previous oeuvre.

The issues at the heart of this film are those which make up the body of his career, freedom, determinism, and the make-up of a human person. That these questions are poorly handled in this film, doesn’t undermine the value that I’ve found in considering them. Which is to say, the best thing about The Host is that it heightened my appreciation for Gattaca.

And that’s a peculiar triumph, one I don’t think we should too easily discard. Making a great film, as Howard Hawks and Ebert remind us, is extremely difficult. The Host is by nowhere close to being a great film, by any definition. But it engages the conversation that Niccol began 16 years ago. And if spending two hours on The Host can further my appreciation for a great film like Gattaca, well, that’s a failure I’m happy to partake in.

Follow The Stake on Twitter and Facebook

A version of this article originally appeared at Hothouse Magazine.

Oh yes, I agree. A wonderful terrible movie. Kind of like the book. A good idea at heart, but the story begs the question of identity by focusing too much on luv and teen ickywick. But I loved the story — loved the idea that a 1000 year old energy force would fall in love with the obsessions of mortality, and that feeling would start a rebellion. Made me think. And I like the connection you make to Gattica. Thanks.

The book was good, the movie stunk. No character development, how could we really care for any of them.

Pingback: Review: Divergent’s on DVD and it’s not all good | The Stake