We’ve come once more to graduation season, and with the delivery of new commencement addresses comes consideration of those past. The most famous commencement speech of recent years must be the author David Foster Wallace’s address to Kenyon College in 2005. Today, Vox ranked the best speeches of the last 50 years, putting Wallace’s speech at #1. TIME did the same last year. Wallace’s speech argues that “capital T Truth is about life before death” and it is, like much of his work, long, funny and dark. It’s a classic.

But it is not the only classic of the commencement speech form. Alyssa Rosenberg, at the Washington Post, thinks that Harry Potter author J.K. Rowlings’s 2008 speech is the best in recent memory.

Yesterday, in a piece about some recent commencement speech invitation controversies, Rosenberg said this about Rowling’s speech:

Rowling challenged the graduates to consider that their résumés and the name of the school on their diplomas would not save them from making grievous mistakes, a point that cannot have been comfortable for the school that issued her invitation.

This message—a diploma, even an Ivy League diploma will not save you from your mistakes—is a profound one for students exiting the halls of learning. This is Harvard, after all, and if any diploma can save one from one’s self, it must be a Harvard diploma. A hard lesson, surely, but that’s what commencement addresses are about: the hard lessons of life.

Both Rowling and Wallace delivered powerful speeches with timeless pearls of wisdom packed between practical advice and philosophical musings. These are the features of great commencement addresses. But Rosenberg’s assertion that “ commencement addresses have been caught up in protest culture” got me thinking about another address delivered to a Harvard graduating class 170 years before J.K. Rowling. One I’d put right at the top of any list of commencement speeches.

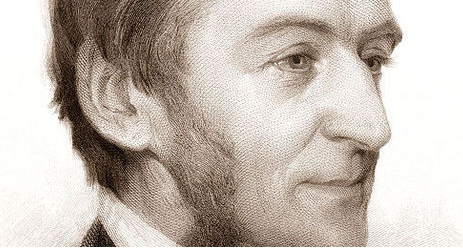

“In this refulgent summer,” Ralph Waldo Emerson said in his 1838 address to the Harvard Divinity School, “it has been a luxury to draw the breath of life.” Thus starts a speech which will praise nature and virtue, refute the presence of Christ’s miracles, call out the priests of a Christian Tradition that needs to be left to history, and dare the audience to “love God, without mediator or veil.”

Rather than reinforce the values of his audience, Emerson sought to direct the efforts and minds of the students of Harvard Divinity School away from the details of history and the promises of religion and towards the present moment of one’s life. Like many great commencement speeches, Emerson’s is long, political, and filled with pithy quotations about life and death (“There is no longer a necessary reason for my being. Already the long shadows of untimely oblivion creep over me, and I shall decease forever.” I mean, that could come right from David Foster Wallace).

It is also, long before the age of internet protest culture, a sermon of protest against a dominant culture of university education, made from the very familiar pulpit of the Commencement Address. Few speeches have had a more lasting effect on American religion than one that told the future priests from Harvard that “the church totters towards its fall”, and “historical Christianity destroys the power of preaching.” The only lasting values that Emerson finds in Christianity are the Sabbath, and “preaching,” speaking one to another, (preaching is “the most flexible of all organs”). Both, Emerson says, are threatened with ruin by the Church.

The concluding advice of Emerson’s address remains as potent today as it was in 1838, and would be right at home in Wallace and Rowling’s speeches. Advising students to live a life of virtue, now, Emerson closes with a call to always speak to others with love, and truth:

“The evils of the church that now is are manifest. The question returns, What shall we do?…Wherever the invitation of men or your own occasions lead you, speak the very truth, as your life and conscience teach it, and cheer the waiting, fainting hearts of men with new hope and new revelation.”

After delivering his address, 30 years would pass before Harvard extended another invitation to Emerson for any purpose. But his speech is still read, and celebrated today. Even Harvard Divinity School celebrates that refulgent summer every July by handing out free popsicles.