Cat’s Cradle is a short book, and a funny one. To those adjectives I would also add: angry, pessimistic, acerbic. It’s a bitter little pill of a novel that can be consumed whole in a single sitting—but though it has its pleasures, it certainly doesn’t go down easy.

Cat’s Cradle is a short book, and a funny one. To those adjectives I would also add: angry, pessimistic, acerbic. It’s a bitter little pill of a novel that can be consumed whole in a single sitting—but though it has its pleasures, it certainly doesn’t go down easy.

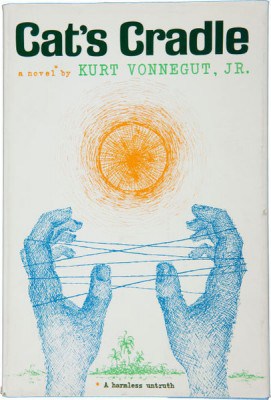

This novel—which was nominated for a Hugo award and which many hold to be Kurt Vonnegut’s best—is the satirist’s take on science and religion, two distinct realms of human endeavor that continue to vie for the power to make and unmake the world to this day. These days, we’re accustomed to people taking one side or the other, throwing in with science’s reliance on evidence and observation to know the natural world, or with religion’s reliance on faith in the supernatural in the absence of conclusive proof. It’s jarring, then, to read the pages of Cat’s Cradle and find that Vonnegut throws in his lot with neither side, but rather—and rather angrily—declares a pox on both houses.

The book begins with the narrator, in an echo of the opening of Moby Dick, asking the reader to “Call me Jonah”—even though his name, he admits, is actually John. John/Jonah has undertaken the writing of a book called The Day the World Ended, about the day the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Research for the book leads him to the late Felix Hoenikker, “The Father of the Atom Bomb.”

Of course, the real-life father of the atom bomb (or one of them, at least) was J. Robert Oppenheimer—a man who, when he saw his creation detonated, thought of the words of the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” In Cat’s Cradle, Felix Hoenikker isn’t nearly as circumspect; when the bomb goes off at Alamogordo test site, a fellow scientist turns to him and says, “Science has now known sin,” to which Vonnegut’s fictional Father of the Atom Bomb replies, “What is sin?”

Before his untimely death, Hoenikker worked at General Forge and Foundry, Vonnegut’s satirization of General Electric. Vonnegut worked at GE in public relations, promoting the research of brilliant scientists who, he felt, were complely indifferent to the ways their discoveries might be used. This is true at General Forge and Foundry too; one of its leaders describes it as a place where “men are paid to increase knowledge, to work toward no end but that.”

Hoenikker is one of these indifferent men paid to increase humankind’s knowledge, and though he’s morally clueless about the consequences of his discoveries, he’s not a bad man. On the contrary, he’s an innocent, driven by his childlike wonder to discover things about the way the world works. Hoenikker’s as likely to research turtles as he is atom bombs. But his boyish curiosity, though it isn’t evil, isn’t simplistically moral either, and eventually it leads him to a discovery that could do even more damage than the atom bomb: ice-nine, a modified water molecule that would instantly harden every body of water on earth.

Vonnegut’s take on religion comes in the form of Bokononism, a fictional faith practiced in the equally fictional banana republic of San Lorenzo. With its own cosmology, rites, sacred texts, and theological terms, Bokononism is a convincingly comprehensive religion, and among Vonnegut’s greatest imaginative creations. In some ways, it’s a religion for people who don’t like religion; The Books of Bokonon begin with the admission that the whole thing is a pack of “foma,” harmless lies. But for those who believe foma and live by them, Bokononism delivers a happy and fulfilling life.

This, then, is Vonnegut’s take on science and religion: one is truth without wisdom, the other occasionally achieves wisdom but doesn’t have a single grain of truth in it.

From this description, you might think that Vonnegut’s being too easy on religion—after all, there are many kinds of religious ideas in the world, many of which are neither wise nor harmless. But as harmless as Bokononism’s foma claim to be, there is something sinister about the religion as well. Bokononism, we later learn, was created by two men who took over the island of San Lorenzo and aspired to create a Utopia there. When they discovered that they couldn’t manage that feat—couldn’t improve the short, brutish lives of San Lorenzans in any meaningful way—they created Bokononism instead, as a means of distracting the islanders from their misery.

Vonnegut’s portrayal of both science and religion is unrelentingly bleak, and as Cat’s Cradle drew to a close, I hoped for some glimmer of hope from the novel. Are morally indifferent truths and pleasant lies to distract us from misery really our only choices?

In the real world, the answer has to be no, otherwise there really is no hope for humanity. But in the world of Cat’s Cradle, at least, a better option never presents itself. The novel’s most enduring sentiment is perhaps the one expressed by a minor character: “Man is vile, and man makes nothing worth making, knows nothing worth knowing.” In Cat’s Cradle, neither science nor religion can save the human race from marching—innocently, irrationally, and blindly—into mass extinction.

If that sounds bleak, it’s important to remember that Vonnegut was writing during a bad time in history. Cat’s Cradle was published in 1963, in the midst of the Cold War and nuclear armament, when science, religion, and nationalism had marched the world to the precipice of destruction. The world was still haunted by the catastrophes at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and by the very real threat of nuclear war. Perhaps Vonnegut would have been more optimistic if he’d been writing today, when fears of nuclear winter have begun to fade from memory.

Or maybe not. More than once as I read, I wondered what Vonnegut would make of today’s scientific and religious landscape. Today, our debates usually focus on truth and progress—whether both can be found in the scientific method, or whether there is something about the universe that will always be unknowable except by faith.

But if Vonnegut—neither a religionist nor a scientist but, above all, a humanist through and through—has anything to teach us, it is that truth alone can’t save us, and that lies, even when they’re harmless, won’t result in human progress either. That’s an important message for our age—and it’s one that keeps Cat’s Cradle relevant in our science-drunk, demon-haunted world.

Follow The Stake on Twitter and Facebook

The Backlist features in-depth appreciations of classic books in the science fiction, fantasy, horror, and crime genres. Click for more in the Backlist series.