*Editor’s Note: This piece originally appeared at Hothouse Magazine.

by Forest Lewis

The general case against Wes Anderson is that he is all style and no content. Any character or narrative depth, any pathos is subsumed and overwhelmed by fussy compositions or cartoony sartorial details. One imagines systematically removing Wes Anderson’s elements of style in order to get to the heart of the matter and finds it can’t be done: if you take away the style you take away the film entire. This does not mean, however, that there was no content there to begin with. Rather, his are movies of which the meaning and the style are inextricable.

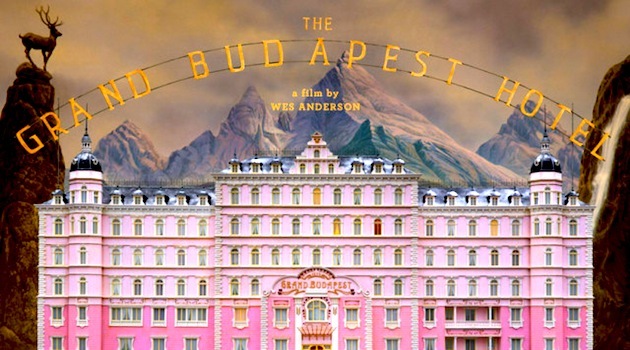

His most recent movie, The Grand Budapest Hotel, is no exception and makes the point clearer. At one hour and forty six minutes the movie is a mad-cap delight, crammed with so much information, so much lavish detail, that you wish you might slow it down for a minute.

Since Fantastic Mr. Fox, Anderson’s films have become more of what they’ve always wanted to be: intricate live-action cartoons—and with a cartoon’s racing sensibility. Here things hum along at a precipitous pace, on a train, on a motorcycle, on skis. Not so much on account of the plot either, but from the sheer quantity of detail in setting, character quirk, in-joke, the little mini stories that happen along the way, all of it rushing from one to the next in a vertiginous manner. Not so quickly, however, as to lose any feeling or significance.

For instance, in the second scene of the movie an elderly author of a book called “The Grand Budapest Hotel” (Tom Wilkonson) is talking to the camera in his study. It is a regal writer’s speech only to be interrupted by a crack and a shriek from the author. The camera moves to the right to reveal a grinning boy holding a toy gun. He dashes away out a door through which painters can be seen on ladders, painting the walls. This is one shot. Next shot contains the author with the boy by his side. The author is stern with the boy, but not too stern; he bears the perfect look of the grandfather who cannot be mad for very long. He continues his speech of reminiscence while the boy stares into the camera, his toy firearm aimed at us. This 35 second moment is entirely captivating.

WA has confessed that he does not first think of the story, but rather, dreams up a setting and a character and adorns details of plot only afterwards. This seems plainly the case in the narrative of TGBH, which lags at times, and at other times seems not to matter much at all in the face of such extravagant and fully dreamed surroundings.

The setting is the titular hotel located in the fictional middle European country of Zubrowka. It is the 1930s and war is on the rise. The palatial hotel is pink and filled with all manner of intricate interiors, and is located on a mountain only accessible by funicular and is not so different from that other idyllic mountain hospice, the sanatorium of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. Both exist in a dreamlike limbo zone, both wish to revoke time.

The story concerns one Gustave H. a concierge of the hotel, played by the wickedly fine Ralph Fiennes. He rules his empire with precision and panache (his cologne is L’Air de Panache) while also bedding all of the elderly dowagers. One of which, known as Madame Celine Villeneuve Desguffe und Taxis (Tilda Swinton), dies suddenly and under suspicious circumstances. She has willed to Gustave H. one “priceless” renaissance painting, “Boy With Apple” (read this amusing article concerning this painting’s historical veracity). Her son, a very foppish and bratty Adrian Brody, contests the will and detests Gustave H. while his enforcer, Willem Defoe, in high Green Goblin mode, enacts vengeance. Redoubtable Gustave H. and his lobby boy apprentice (Tony Revolori) steal the painting and thus kick the rickety plot into high gear. But never mind the ricketiness, the movie is a romp.

And a violent romp it is. Fingers and a head are severed. Heads are clubbed with rifle butts. Cats are defenestrated. This must be WA’s most gruesome movie yet. A gruesomeness too that is not quelled by its cuteness. So too the fashionable pseudo Nazi’s that show up to menace our heroes.

These fascists are lead by Edward Norton and are dressed in the sharpest fascist uniforms of all time. But aren’t the Nazis always the most fashionable oppressors? And isn’t it rather typical of the movies to show off the cut of Nazi dress? As if to say, Nazi’s really were horrible, but didn’t they look just great? Fascism/fashion: here the association is not so absurd—so Giacomo Leopardi’s “Fashion is the mother of death.” These fascists, however, are removed from history—one might say that the whole movie is anti-historical—for their symbol is not the swastika, but rather a double Z. They are less fascist than quite simply a physical embodiment of brute change. Our magical and idyllic hotel cannot last forever.

This is the emotional center of the movie and it works. Gustave is heroic for attempting to preserve a lost moment in time. He is described as being a man out-of-time hoping to preserve ideals that may never have been. He’s one that might serve as a hero for WA’s entire work. These movies do not only concern nostalgia, but rather, a nostalgia for a place that never existed. This proves, in the end, the practical and symbolical implications of WA’s heavy style. One might view all of his movies as elaborate memories—for aren’t our memories but stylized fantasies that we embellish and perfect over time?

In this sense the “Boy With Apple” painting and the boy pointing his gun at us takes on considerable weight. One of them embodies an ideal that we once knew, or at least have imagined, the other is the waiting inheritor, the youth that will usurp us. The glimmer of hope is that not all is lost to the dragon of time; the youth does inherit something, even if it is as small as a book, or a painting, or even a movie. In the worlds of Wes Anderson the past is artifice.

Follow The Stake on Twitter and Facebook

Forest Lewis is a carpenter/writer living in Minneapolis. He writes a weekly horoscope for Revolver. Those can be found here. Follow him on Twitter @interrogativs

[…] for Wes Anderson here at the Stake. He weaves a potent spell of nostalgia in all his films – even nostalgia for pasts that have never existed. Moonrise Kingdom, his 2013 gem, played out in era of Anderson’s own longing and creation. In its […]