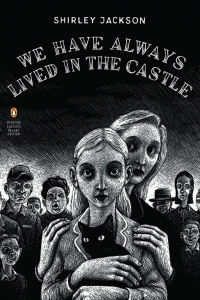

It’s been two weeks since I finished Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and I still can’t figure out how she did it. How did Shirley Jackson scare me so much, with nothing more than grocery lists, visits to the library, tea parties, and languid walks in the woods? This was one of the most profoundly unsettling books I’ve ever experienced—yet when I try to think about exactly what about the book disturbed me so, I can’t put my finger on it. Which is, perhaps, precisely the point: Jackson’s great skill is in locating the unsettling in the midst of the mundane, the horror in the banal.

It’s been two weeks since I finished Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and I still can’t figure out how she did it. How did Shirley Jackson scare me so much, with nothing more than grocery lists, visits to the library, tea parties, and languid walks in the woods? This was one of the most profoundly unsettling books I’ve ever experienced—yet when I try to think about exactly what about the book disturbed me so, I can’t put my finger on it. Which is, perhaps, precisely the point: Jackson’s great skill is in locating the unsettling in the midst of the mundane, the horror in the banal.

Jackson is, of course, the author of “The Lottery,” the chilling short story that shocked and scandalized readers when it was published in The New Yorker in 1948. Today, the story that was widely condemned as perverse is regularly read by high school students across the nation. Public perception of vulgarity moves quickly, I guess—yet there’s still something delightfully transgressive about the tale. Most everyone’s read it, yet I hesitate to spoil it for the few people out there who might not have (if this is you, I beg you, find a copy and read it immediately; I’ll wait). Even in an age of graphic primetime violence and popular novel trilogies featuring children fighting to the death, “The Lottery” hasn’t lost its capacity to shock; its portrayal of small-town manners interrupted by an outburst of ritualistic violence remains one of the great narrative fake-outs in the history of storytelling.

There’s something similarly, and deliciously, perverse about We Have Always Lived in the Castle—but where “The Lottery” leveraged its mix of monstrosity and mundanity for a bright splash of shock and horror, Castle‘s colors are more muted, evocative of a sort of low-level dread, a constant thrum of prevasive wrongness that had me practically nauseated as I read.

The combined mundanity and oddity of this novel—novella, really—is evident from the very first paragraph. It begins simply enough: “My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance.” But then a powerful strangeness begins to assert itself in the next sentence, when Mary Katherine—or Merricat, as she is nicknamed—says that she wishes she had been “born a werewolf.” She goes on to express an affinity for “Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom,” and concludes with the simple statement: “Everyone else in my family is dead.”

This first paragraph is, essentially, the entirety of the novel contained in miniature, though Jackson deftly covers the information communicated in this opening—the frozen childhood, the whimsically creepy interest in sympathetic magic, the obsession with poison and death—with the everyday: Merricat’s visit to town, her private rituals to ward off the attention of the townspeople, and her escape back to the isolated Blackwood mansion to be with her sister.

Strictly speaking, not much happens in Castle. The isolation of Merricat and Constance in the mansion, their state of eerie emotional stasis, is precisely the point. There are hints of a crisis in the past—the Blackwood family was poisoned years earlier with arsenic-laced berries, and Constance was tried and acquitted of the crime. Since then, the house has become a castle of solitude, a kingdom ruled over by Constance, who busies herself in the kitchen, the site of the primal crime; Uncle Julian, who labors endlessly on a book reliving the meal that killed his wife and confined him to a wheelchair; and Merricat, who wards off change with talismans littered across the house and grounds: silver dollars buried in the garden, a book nailed to a tree.

When Constance’s and Merricat’s cousin Charles comes calling, his presence is a threat to Merricat’s carefully-constructed equilibrium. It’s not clear whether he’s interested in Constance’s hand in marriage or their parents’ fortune. Perhaps both. Either way, his presence is the variable that tips the delicate balance of family dysfunction within and community resentment without—with shocking results that I will not reveal.

We Have Always Lived in the Castle is a horror story of sorts—yet there’s very little magic, violence, or overt horror, and the details of the story are more evocative of a domestic novel. Merricat, as she’s trying to drive out Charles from the house, calls him a “ghost”—yet it’s she and Constance who are the ghosts, and the contours of their everyday lives that are truly terrifying: the stultifying atmosphere of the close-minded small town, their domestic imprisonment as women inside their family home, and the mutual complicity of their relationship with one another.

It’s brilliant, and scary, and a horror book like no other. In Jackson’s world, it isn’t houses that are haunted. It’s people.