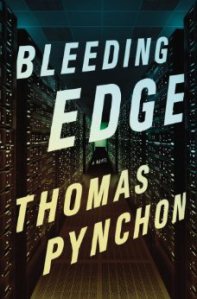

Early reviews for Thomas Pynchon’s new novel, Bleeding Edge, are starting to trickle in, and they’re pretty stellar.

Early reviews for Thomas Pynchon’s new novel, Bleeding Edge, are starting to trickle in, and they’re pretty stellar.

Bleeding Edge is about a New York private eye named Maxine Tarnow, who begins investigating mysterious goings-on at a computer security firm and promptly, as PIs always must in stories like these, gets in over her head. The last time Pynchon wrote about a PI it was in his previous novel, Inherent Vice, which got pegged by the critics as minor Pynchon, not among his best novels. Based on the plot synopsis alone, I had suspected that this novel would be more of the same.

Not so, say the early reviews. Set in 2001, Bleeding Edge takes place in the…well…bleeding edge between two American wounds: the dot-com bubble and the attack on the World Trade Center. Slate’s Troy Patterson calls it “the 9/11 novel you never knew you needed.”

Here’s David Kipen in Publisher’s Weekly, on the world-historical ambition of this hardboiled detective novel:

Almost all Pynchon’s books are historical novels, with this one no exception. Where Vineland slyly set a story of Orwellian government surveillance in 1984, Bleeding Edge situates a fable of increasingly sentient computers in, naturally, 2001. Of course, the year 2001 means something besides HAL and Dave now, and Pynchon spirits us through “that terrible morning” in September-and its “infantilizing” aftermath-with unhysterical grace.

And here’s Patterson again, on the novel’s pleasures and its importance:

Bleeding Edge is not so major a book as [V., Gravity's Rainbow, or Mason & Dixon]. It’s more on the order of Vineland—a genre-drunk, ganja-fried study of place and paranoid mood, with a certain ceiling on its explorations of character, a lovely unconcern for those snoots who find its meta-pop sensibilities lacking, and down the home stretch a laggardly quality as the narrative threads of its shaggy-dog subplots get matted. But it strikes me as a necessary novel and one that literary history has been waiting for, ever since it went to bed early on innocent Sept. 10 with a copy of The Corrections and stayed up well past midnight reading Franzen into the wee hours of his novel’s publication day. As I recall, literary history then slept in and woke to an alarmed answering machine exclaiming rare questions and soon was on the roof in Brooklyn, where people watched the “terminal plume” (as Pynchon calls it) from across the river—“from a place of safety they no longer believed in.”

A “genre-drunk” novel that is simultaneously the “one that literary history has been waiting for”? Yes, please! Someone get me a copy of this book, like now.